The profound connection between dietary patterns and visual health has been firmly established through decades of scientific research. As the global population ages and digital screen usage intensifies, the importance of nutritional interventions for preserving eyesight has never been more critical. The World Health Organization identifies age-related eye diseases as significant contributors to visual impairment worldwide, with cataracts accounting for 33% and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) representing 1% of these cases 1 Fortunately, substantial evidence demonstrates that specific dietary components can directly support ocular structure and function, potentially reducing the risk of these vision-threatening conditions.

Key nutrients play a vital role in maintaining vision across life stages. Lutein and zeaxanthin, carotenoids concentrated in the macula, act as natural blue-light filters and antioxidants that protect retinal tissues 2 Vitamin A and beta-carotene support retinal function and prevent night blindness, while vitamin C strengthens ocular blood vessels and may reduce cataract risk. Zinc aids vitamin A transport, and omega-3 fatty acids help maintain retinal structure and function, 3

4 Constant light exposure generates oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage retinal cells. Carotenoids like lutein protect by filtering blue light and neutralizing free radicals 5 6 Phytochemicals such as sulforaphane in broccoli activate NRF2 antioxidant pathways, and anthocyanins enhance ocular blood flow 7 8 Together, these nutrients highlight why consuming diverse vegetables is superior to isolated supplements.

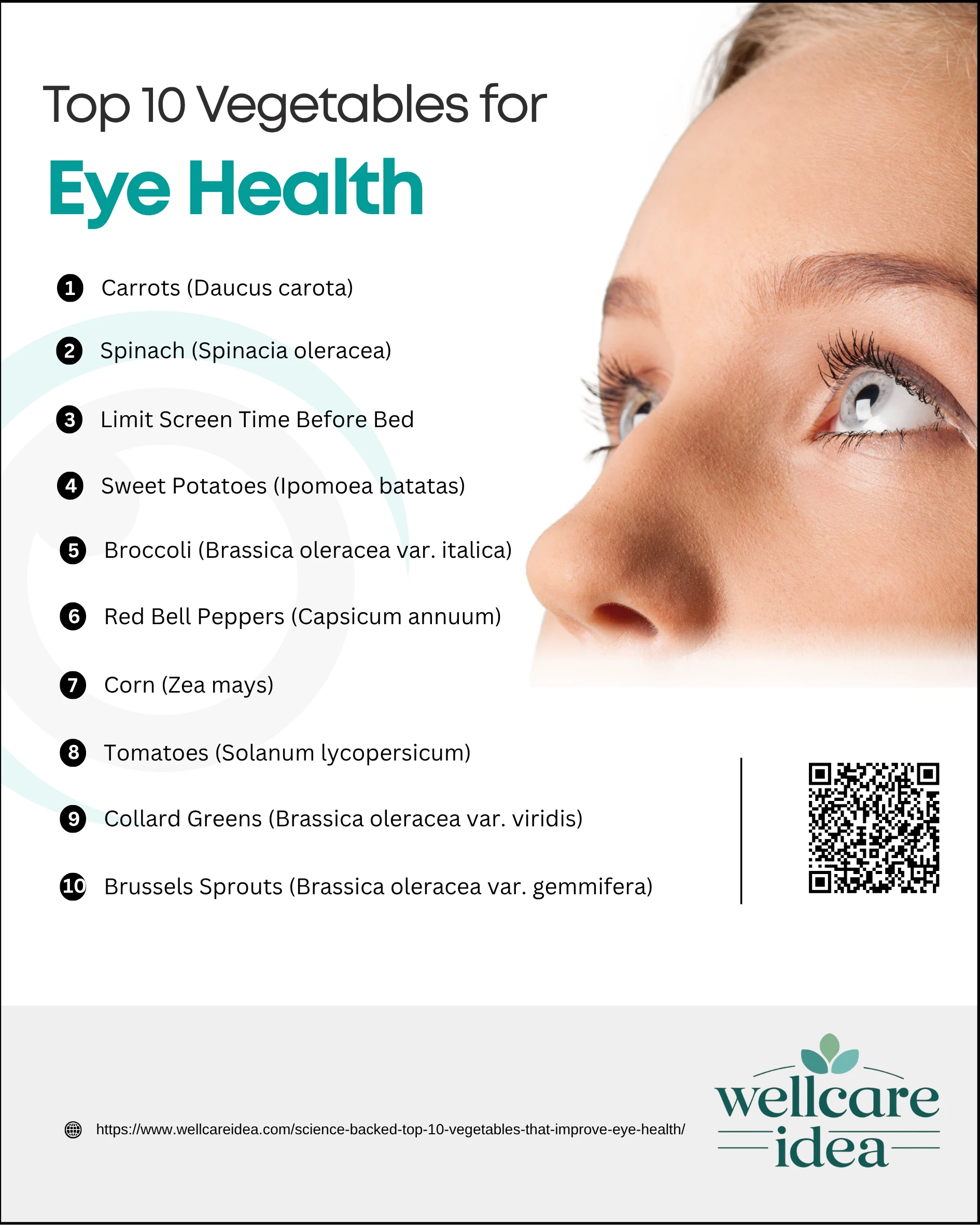

Science-Backed Top 10 Vegetables for Eye Health

Science-Backed Top 10 Vegetables for Eye Health

1. Carrots (Daucus carota)

Carrots have long been celebrated for their vision-supporting properties, primarily due to their high beta-carotene content. This provitamin A carotenoid is converted to retinol in the body, which is essential for the formation of rhodopsin, a photopigment in the retina that enables vision in low-light conditions 9 Scientific evidence confirms that vitamin A deficiency can lead to night blindness and, in severe cases, complete vision loss due to corneal damage 10 A single baked sweet potato provides over 560% of the daily value for vitamin A, 11 demonstrating the potent bioavailability of plant-based provitamin A carotenoids.

While cooking carrots slightly reduces their vitamin C content, it significantly enhances the bioavailability of beta-carotene by breaking down cell walls. For optimal absorption, consume carrots with a source of healthy fat, such as olive oil or avocado. Incorporating cooked, pureed carrots into soups, sauces, or baked goods provides an excellent way to obtain their vision-protecting benefits while appealing to diverse palates.

2. Spinach (Spinacia oleracea)

Spinach serves as an exceptional source of macular carotenoids, containing approximately 59-79 micrograms of lutein per gram dry weight 12 These carotenoids accumulate in the central retina where they filter blue light and neutralize free radicals generated by photo-oxidative stress. Regular consumption of spinach and other leafy greens has been associated with a significantly reduced risk of developing age-related macular degeneration, with some studies indicating risk reductions of 18-25% among high consumers 13

The method of preparation influences the bioavailability of spinach’s carotenoids. Light cooking helps break down cell walls and increases carotenoid absorption, while simultaneously reducing the vegetable’s volume, enabling consumption of larger quantities. However, consuming raw spinach in salads still provides valuable nutrients, especially when paired with a healthy fat source like olive oil-based dressing to enhance fat-soluble carotenoid absorption. Combining spinach with eggs, which naturally contain lutein and zeaxanthin in a highly bioavailable matrix, creates a synergistic effect for macular pigment enhancement.

3. Kale (Brassica oleracea var. sabellica)

Kale stands out as one of the most concentrated dietary sources of lutein and zeaxanthin, containing 48-115 micrograms per gram dry weight 14 These xanthophyll carotenoids selectively concentrate in the macula where they form the macular pigment, a protective layer that filters harmful high-energy blue light and provides antioxidant defense against photo-oxidative damage 15 Research indicates that higher macular pigment optical density is associated with improved visual performance and reduced risk for age-related macular degeneration 16

A randomized controlled trial published in Frontiers in Nutrition demonstrated that supplementation with lutein and zeaxanthin isomers (10mg and 2mg daily) significantly improved several objective measures of eye health in high electronic screen users, including tear production and photo-stress recovery time 17

o maximize kale’s benefits, consume it with healthy fats and consider lightly steaming rather than eating raw to improve carotenoid bioavailability.

4. Sweet Potatoes (Ipomoea batatas)

Orange-fleshed sweet potatoes represent a remarkable source of beta-carotene, which the body converts to vitamin A, a nutrient essential for maintaining the eye’s surface integrity and supporting retinal function 18 The vibrant orange color directly correlates with beta-carotene concentration, with deeper orange varieties containing higher levels of this provitamin A carotenoid. Research conducted in South Africa has demonstrated that regular consumption of specific sweet potato varieties can provide over 100% of daily vitamin A requirements for children, making them a powerful food-based approach to combating deficiency-related blindness 19

In addition to beta-carotene, sweet potatoes contain vitamin E, another fat-soluble antioxidant that works synergistically with other nutrients to protect cell membranes from oxidative damage 20

For optimal nutrient absorption, consume cooked sweet potatoes with a source of dietary fat, such as coconut oil or nuts. Roasting brings out their natural sweetness while preserving more nutrients compared to boiling.

5. Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica)

Broccoli contains a powerful phytochemical system centered around sulforaphane, an isothiocyanate derived from its precursor glucoraphanin 8 This compound activates the NRF2 pathway, a master regulator of cellular antioxidant defenses that enhances the expression of multiple genes encoding antioxidant enzymes and phase II detoxification proteins 21 In retinal cells, this pathway helps neutralize oxidative stress generated by constant exposure to light and high oxygen tension, thereby protecting against degenerative processes.

Beyond its sulforaphane content, broccoli provides substantial amounts of vitamin C, which concentrates in the aqueous humor of the eye where it protects against UV-induced oxidative damage 22 Epidemiological studies have demonstrated inverse correlations between dietary vitamin C intake and cataract risk, with the highest consumers showing up to 45% reduced risk of posterior subcapsular cataracts compared to low consumers 23 To preserve broccoli’s heat-sensitive nutrients, consider steaming rather than boiling, and include the florets and leaves where glucoraphanin is most concentrated.

6. Red Bell Peppers (Capsicum annuum)

Red bell peppers provide an exceptional source of vitamin C, containing significantly higher concentrations than their green or yellow counterparts 24 This water-soluble antioxidant plays a crucial role in ocular health by protecting proteins in the lens from oxidation, thereby potentially reducing the risk of cataract development 4 The human eye maintains vitamin C concentrations in the aqueous humor that exceed plasma levels by 15-20 fold, indicating an active transport mechanism and suggesting critical physiological functions 25

In addition to their impressive vitamin C content, red bell peppers contain zeaxanthin, a macular carotenoid that complements the antioxidant system 15 While zeaxanthin is less abundant in most commonly consumed vegetables compared to lutein, red peppers represent one of the richer dietary sources

Since vitamin C is heat-sensitive, consuming red peppers raw in salads or as snacks preserves this nutrient, while light cooking can enhance the bioavailability of their carotenoids.

7. Corn (Zea mays)

Corn represents a significant dietary source of zeaxanthin, particularly in populations where it serves as a staple food. The specific carotenoid profile of corn includes zeaxanthin in relatively high concentrations, with corn tortillas containing approximately 105 micrograms per gram dry weight and corn chips about 93 micrograms 15 This is noteworthy because zeaxanthin, along with its isomer lutein, selectively accumulates in the macular region of the retina where it contributes to the protective macular pigment 2

Research examining the relationship between dietary patterns and visual function has revealed that regular consumption of zeaxanthin-rich foods like corn may help maintain macular pigment density, which serves as a biomarker for visual health and AMD risk 16 The processing method influences carotenoid bioavailability, with traditional nixtamalization (alkaline cooking) enhancing zeaxanthin absorption from corn products.

Combining corn with healthy fats, such as in salads with olive oil dressing, further optimizes the bioavailability of its fat-soluble carotenoids.

8. Tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum)

Tomatoes are renowned for their lycopene content, a carotenoid pigment that provides their characteristic red color. Although lycopene does not concentrate specifically in the macular region like lutein and zeaxanthin, it functions as a potent antioxidant throughout the body, including ocular tissues 26 Lycopene’s extensive system of conjugated double bonds makes it particularly effective at quenching singlet oxygen, a type of free radical generated by exposure to light 27

Processing tomatoes significantly enhances lycopene bioavailability, with cooked tomato products like sauce and paste containing higher bioavailable lycopene than fresh tomatoes 28 The addition of healthy fats, such as olive oil, further improves absorption of this fat-soluble carotenoid.

9. Collard Greens (Brassica oleracea var. viridis)

Collard greens provide an excellent source of lutein and zeaxanthin, placing them among the most nutrient-dense leafy greens for supporting macular health 29 These carotenoids accumulate in the retina where they serve dual protective functions: filtering harmful high-energy blue light and neutralizing reactive oxygen species generated by photo-oxidative stress 15 Epidemiological evidence suggests that diets rich in these carotenoids are associated with reduced risk of advanced age-related macular degeneration, particularly the more severe neovascular form 13

Regular consumption of collard greens may contribute to the maintenance of macular pigment optical density (MPOD), which is increasingly recognized as an important biomarker for visual health and function 16 The fiber content in collard greens may also indirectly support eye health by promoting cardiovascular function and healthy blood flow to ocular tissues. For optimal nutrient retention, consider steaming rather than boiling, and combine with a source of monounsaturated fat, such as olive oil, to enhance carotenoid absorption.

10. Brussels Sprouts (Brassica oleracea var. gemmifera)

Brussels sprouts contain a powerful combination of eye-supporting nutrients, including vitamin C, vitamin A, and various antioxidant compounds 30 The high vitamin C content contributes to the maintenance of healthy blood vessels in the eye and supports the regeneration of other antioxidants, such as vitamin E 4 Additionally, Brussels sprouts provide glucosinolates that can be converted to isothiocyanates like sulforaphane, which activates cellular defense mechanisms against oxidative stress 8

The antioxidant protection offered by Brussels sprouts may help reduce the risk of cataract formation by preventing oxidative damage to lens proteins 23

Cooking methods influence both the availability of these protective compounds and their palatability. Roasting enhances their natural sweetness while preserving more nutrients than boiling.

Table: Eye-Health Supporting Vegetables and Their Key Nutrients

| Vegetable | Key Nutrients | Eye Health Benefit | |

| Carrots 9 | Beta-carotene | Supports retinal function and night vision | |

| Spinach 13 | Lutein, Zeaxanthin | Reduces AMD risk, protects macula | |

| Kale 15 | Lutein, Zeaxanthin | Filters blue light, antioxidant protection | |

| Sweet Potatoes 18 | Beta-carotene, Vitamin E | Prevents vitamin A deficiency, supports eye surface | |

| Broccoli 8 | Vitamin C, Sulforaphane | Activates NRF2 pathway, antioxidant defense | |

| Red Bell Peppers 4 | Vitamin C, Zeaxanthin | Reduces cataract risk, antioxidant protection | |

| Corn 16 | Zeaxanthin | Maintains macular pigment density | |

| Tomatoes 26 | Lycopene | Protects against light-induced damage | |

| Collard Greens 15 | Lutein, Zeaxanthin | Supports retinal health, oxidative protection | |

Other Vegetables Beneficial for Eye Health

Beyond the top ten vegetables highlighted, several others deserve recognition for their vision-supporting properties. Green peas provide valuable lutein and zeaxanthin in addition to their protein and fiber content 31Turnip greens and beet greens offer similar nutritional profiles to collard greens and kale, containing substantial amounts of lutein and other carotenoids 32 Zucchini contributes modest amounts of antioxidants and can be easily incorporated into various dishes due to its mild flavor. 33

The scientific evidence overwhelmingly supports the profound impact of vegetable consumption on visual health and protection against degenerative eye diseases. The unique combination of carotenoids, vitamins, and phytochemicals found in vegetables works through multiple complementary mechanisms to preserve vision across the lifespan. From the blue-light filtering capacity of lutein and zeaxanthin to the antioxidant power of vitamins C and E and the cellular protection offered by sulforaphane, these natural compounds provide a sophisticated defense system against environmental insults and age-related degeneration.